Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Other fields of psychology: AI · Computer · Consulting · Consumer · Engineering · Environmental · Forensic · Military · Sport · Transpersonal · Index

Automated information coding is an aspect of automated information processing and is he use of computers to retrieve data automatically. Information retrieval is the activity of obtaining information resources relevant to an information need from a collection of information resources. Searches can be based on metadata or on full-text (or other content-based) indexing.

Automated information retrieval systems are used to reduce what has been called "information overload". Many universities and public libraries use IR systems to provide access to books, journals and other documents. Web search engines are the most visible IR applications.

History[]

| “ | But do you know that, although I have kept the diary [on a phonograph] for months past, it never once struck me how I was going to find any particular part of it in case I wanted to look it up? | ” |

—Dr Seward, Bram Stoker's Dracula, 1897 | ||

The idea of using computers to search for relevant pieces of information was popularized in the article As We May Think by Vannevar Bush in 1945.[1] The first automated information retrieval systems were introduced in the 1950s and 1960s. By 1970 several different techniques had been shown to perform well on small text corpora such as the Cranfield collection (several thousand documents).[1] Large-scale retrieval systems, such as the Lockheed Dialog system, came into use early in the 1970s.

In 1992, the US Department of Defense along with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), cosponsored the Text Retrieval Conference (TREC) as part of the TIPSTER text program. The aim of this was to look into the information retrieval community by supplying the infrastructure that was needed for evaluation of text retrieval methodologies on a very large text collection. This catalyzed research on methods that scale to huge corpora. The introduction of web search engines has boosted the need for very large scale retrieval systems even further.

Timeline[]

- Before the 1900s

- 1801: Joseph Marie Jacquard invents the Jacquard loom, the first machine to use punched cards to control a sequence of operations.

- 1880s: Herman Hollerith invents an electro-mechanical data tabulator using punch cards as a machine readable medium.

- 1890 Hollerith cards, keypunches and tabulators used to process the 1890 US Census data.

- 1920s-1930s

- Emanuel Goldberg submits patents for his "Statistical Machine” a document search engine that used photoelectric cells and pattern recognition to search the metadata on rolls of microfilmed documents.

- 1940s–1950s

- late 1940s: The US military confronted problems of indexing and retrieval of wartime scientific research documents captured from Germans.

- 1945: Vannevar Bush's As We May Think appeared in Atlantic Monthly.

- 1947: Hans Peter Luhn (research engineer at IBM since 1941) began work on a mechanized punch card-based system for searching chemical compounds.

- 1950s: Growing concern in the US for a "science gap" with the USSR motivated, encouraged funding and provided a backdrop for mechanized literature searching systems (Allen Kent et al.) and the invention of citation indexing (Eugene Garfield).

- 1950: The term "information retrieval" appears to have been coined by Calvin Mooers.[2]

- 1951: Philip Bagley conducted the earliest experiment in computerized document retrieval in a master thesis at MIT.[3]

- 1955: Allen Kent joined Case Western Reserve University, and eventually became associate director of the Center for Documentation and Communications Research. That same year, Kent and colleagues published a paper in American Documentation describing the precision and recall measures as well as detailing a proposed "framework" for evaluating an IR system which included statistical sampling methods for determining the number of relevant documents not retrieved.

- 1958: International Conference on Scientific Information Washington DC included consideration of IR systems as a solution to problems identified. See: Proceedings of the International Conference on Scientific Information, 1958 (National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, 1959)

- 1959: Hans Peter Luhn published "Auto-encoding of documents for information retrieval."

- late 1940s: The US military confronted problems of indexing and retrieval of wartime scientific research documents captured from Germans.

- 1960s:

- early 1960s: Gerard Salton began work on IR at Harvard, later moved to Cornell.

- 1960: Melvin Earl Maron and John Lary Kuhns[4] published "On relevance, probabilistic indexing, and information retrieval" in the Journal of the ACM 7(3):216–244, July 1960.

- 1962:

- Cyril W. Cleverdon published early findings of the Cranfield studies, developing a model for IR system evaluation. See: Cyril W. Cleverdon, "Report on the Testing and Analysis of an Investigation into the Comparative Efficiency of Indexing Systems". Cranfield Collection of Aeronautics, Cranfield, England, 1962.

- Kent published Information Analysis and Retrieval.

- 1963:

- Weinberg report "Science, Government and Information" gave a full articulation of the idea of a "crisis of scientific information." The report was named after Dr. Alvin Weinberg.

- Joseph Becker and Robert M. Hayes published text on information retrieval. Becker, Joseph; Hayes, Robert Mayo. Information storage and retrieval: tools, elements, theories. New York, Wiley (1963).

- 1964:

- Karen Spärck Jones finished her thesis at Cambridge, Synonymy and Semantic Classification, and continued work on computational linguistics as it applies to IR.

- The National Bureau of Standards sponsored a symposium titled "Statistical Association Methods for Mechanized Documentation." Several highly significant papers, including G. Salton's first published reference (we believe) to the SMART system.

- mid-1960s:

- National Library of Medicine developed MEDLARS Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System, the first major machine-readable database and batch-retrieval system.

- Project Intrex at MIT.

- 1965: J. C. R. Licklider published Libraries of the Future.

- 1966: Don Swanson was involved in studies at University of Chicago on Requirements for Future Catalogs.

- late 1960s: F. Wilfrid Lancaster completed evaluation studies of the MEDLARS system and published the first edition of his text on information retrieval.

- 1968:

- Gerard Salton published Automatic Information Organization and Retrieval.

- John W. Sammon, Jr.'s RADC Tech report "Some Mathematics of Information Storage and Retrieval..." outlined the vector model.

- 1969: Sammon's "A nonlinear mapping for data structure analysis" (IEEE Transactions on Computers) was the first proposal for visualization interface to an IR system.

- 1970s

- early 1970s:

- First online systems—NLM's AIM-TWX, MEDLINE; Lockheed's Dialog; SDC's ORBIT.

- Theodor Nelson promoting concept of hypertext, published Computer Lib/Dream Machines.

- 1971: Nicholas Jardine and Cornelis J. van Rijsbergen published "The use of hierarchic clustering in information retrieval", which articulated the "cluster hypothesis."[5]

- 1975: Three highly influential publications by Salton fully articulated his vector processing framework and term discrimination model:

- A Theory of Indexing (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics)

- A Theory of Term Importance in Automatic Text Analysis (JASIS v. 26)

- A Vector Space Model for Automatic Indexing (CACM 18:11)

- 1978: The First ACM SIGIR conference.

- 1979: C. J. van Rijsbergen published Information Retrieval (Butterworths). Heavy emphasis on probabilistic models.

- early 1970s:

- 1980s

- 1980: First international ACM SIGIR conference, joint with British Computer Society IR group in Cambridge.

- 1982: Nicholas J. Belkin, Robert N. Oddy, and Helen M. Brooks proposed the ASK (Anomalous State of Knowledge) viewpoint for information retrieval. This was an important concept, though their automated analysis tool proved ultimately disappointing.

- 1983: Salton (and Michael J. McGill) published Introduction to Modern Information Retrieval (McGraw-Hill), with heavy emphasis on vector models.

- 1985: David Blair and Bill Maron publish: An Evaluation of Retrieval Effectiveness for a Full-Text Document-Retrieval System

- mid-1980s: Efforts to develop end-user versions of commercial IR systems.

- 1985–1993: Key papers on and experimental systems for visualization interfaces.

- Work by Donald B. Crouch, Robert R. Korfhage, Matthew Chalmers, Anselm Spoerri and others.

- 1989: First World Wide Web proposals by Tim Berners-Lee at CERN.

- 1990s

- 1992: First TREC conference.

- 1997: Publication of Korfhage's Information Storage and Retrieval[6] with emphasis on visualization and multi-reference point systems.

- late 1990s: Web search engines implementation of many features formerly found only in experimental IR systems. Search engines become the most common and maybe best instantiation of IR models, research, and implementation.

Overview[]

An information retrieval process begins when a user enters a query into the system. Queries are formal statements of information needs, for example search strings in web search engines. In information retrieval a query does not uniquely identify a single object in the collection. Instead, several objects may match the query, perhaps with different degrees of relevancy.

An object is an entity that is represented by information in a database. User queries are matched against the database information. Depending on the application the data objects may be, for example, text documents, images,[7] audio,[8] mind maps[9] or videos. Often the documents themselves are not kept or stored directly in the IR system, but are instead represented in the system by document surrogates or metadata.

Most IR systems compute a numeric score on how well each object in the database matches the query, and rank the objects according to this value. The top ranking objects are then shown to the user. The process may then be iterated if the user wishes to refine the query.[10]

Performance and correctness measures[]

- Main article: Precision and recall

Many different measures for evaluating the performance of information retrieval systems have been proposed. The measures require a collection of documents and a query. All common measures described here assume a ground truth notion of relevancy: every document is known to be either relevant or non-relevant to a particular query. In practice queries may be ill-posed and there may be different shades of relevancy.

Precision[]

Precision is the fraction of the documents retrieved that are relevant to the user's information need.

In binary classification, precision is analogous to positive predictive value. Precision takes all retrieved documents into account. It can also be evaluated at a given cut-off rank, considering only the topmost results returned by the system. This measure is called precision at n or P@n.

Note that the meaning and usage of "precision" in the field of Information Retrieval differs from the definition of accuracy and precision within other branches of science and technology.

Recall[]

Recall is the fraction of the documents that are relevant to the query that are successfully retrieved.

In binary classification, recall is often called sensitivity. So it can be looked at as the probability that a relevant document is retrieved by the query.

It is trivial to achieve recall of 100% by returning all documents in response to any query. Therefore recall alone is not enough but one needs to measure the number of non-relevant documents also, for example by computing the precision.

Fall-out[]

The proportion of non-relevant documents that are retrieved, out of all non-relevant documents available:

In binary classification, fall-out is closely related to specificity and is equal to . It can be looked at as the probability that a non-relevant document is retrieved by the query.

It is trivial to achieve fall-out of 0% by returning zero documents in response to any query.

F-measure[]

- Main article: F-score

The weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall, the traditional F-measure or balanced F-score is:

This is also known as the measure, because recall and precision are evenly weighted.

The general formula for non-negative real is:

- .

Two other commonly used F measures are the measure, which weights recall twice as much as precision, and the measure, which weights precision twice as much as recall.

The F-measure was derived by van Rijsbergen (1979) so that "measures the effectiveness of retrieval with respect to a user who attaches times as much importance to recall as precision". It is based on van Rijsbergen's effectiveness measure . Their relationship is where .

Average precision[]

Precision and recall are single-value metrics based on the whole list of documents returned by the system. For systems that return a ranked sequence of documents, it is desirable to also consider the order in which the returned documents are presented. By computing a precision and recall at every position in the ranked sequence of documents, one can plot a precision-recall curve, plotting precision as a function of recall . Average precision computes the average value of over the interval from to :[11]

That is the area under the precision-recall curve. This integral is in practice replaced with a finite sum over every position in the ranked sequence of documents:

where is the rank in the sequence of retrieved documents, is the number of retrieved documents, is the precision at cut-off in the list, and is the change in recall from items to .[11]

This finite sum is equivalent to:

where is an indicator function equaling 1 if the item at rank is a relevant document, zero otherwise.[12] Note that the average is over all relevant documents and the relevant documents not retrieved get a precision score of zero.

Some authors choose to interpolate the function to reduce the impact of "wiggles" in the curve.[13][14] For example, the PASCAL Visual Object Classes challenge (a benchmark for computer vision object detection) computes average precision by averaging the precision over a set of evenly spaced recall levels {0, 0.1, 0.2, ... 1.0}[13][14]:

where is an interpolated precision that takes the maximum precision over all recalls greater than :

- .

An alternative is to derive an analytical function by assuming a particular parametric distribution for the underlying decision values. For example, a binormal precision-recall curve can be obtained by assuming decision values in both classes to follow a Gaussian distribution.[15]

R-Precision[]

Precision at R-th position in the ranking of results for a query that has R relevant documents. This measure is highly correlated to Average Precision. Also, Precision is equal to Recall at the R-th position.

Mean average precision[]

Mean average precision for a set of queries is the mean of the average precision scores for each query.

where Q is the number of queries.

Discounted cumulative gain[]

- Main article: Discounted cumulative gain

DCG uses a graded relevance scale of documents from the result set to evaluate the usefulness, or gain, of a document based on its position in the result list. The premise of DCG is that highly relevant documents appearing lower in a search result list should be penalized as the graded relevance value is reduced logarithmically proportional to the position of the result.

The DCG accumulated at a particular rank position is defined as:

Since result set may vary in size among different queries or systems, to compare performances the normalised version of DCG uses an ideal DCG. To this end, it sorts documents of a result list by relevance, producing an ideal DCG at position p (), which normalizes the score:

The nDCG values for all queries can be averaged to obtain a measure of the average performance of a ranking algorithm. Note that in a perfect ranking algorithm, the will be the same as the producing an nDCG of 1.0. All nDCG calculations are then relative values on the interval 0.0 to 1.0 and so are cross-query comparable.

Other Measures[]

- Mean reciprocal rank

- Spearman's rank correlation coefficient

Model types[]

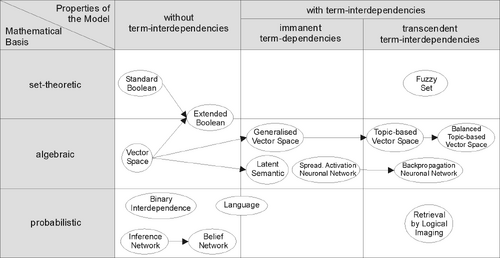

Categorization of IR-models (translated from German entry, original source Dominik Kuropka).

For effectively retrieving relevant documents by IR strategies, the documents are typically transformed into a suitable representation. Each retrieval strategy incorporate a specific model for its document representation purposes. The picture on the right illustrates the relationship of some common models. In the picture, the models are categorized according to two dimensions: the mathematical basis and the properties of the model.

First dimension: mathematical basis[]

- Set-theoretic models represent documents as sets of words or phrases. Similarities are usually derived from set-theoretic operations on those sets. Common models are:

- Standard Boolean model

- Extended Boolean model

- Fuzzy retrieval

- Algebraic models represent documents and queries usually as vectors, matrices, or tuples. The similarity of the query vector and document vector is represented as a scalar value.

- Vector space model

- Generalized vector space model

- (Enhanced) Topic-based Vector Space Model

- Extended Boolean model

- Latent semantic indexing aka latent semantic analysis

- Probabilistic models treat the process of document retrieval as a probabilistic inference. Similarities are computed as probabilities that a document is relevant for a given query. Probabilistic theorems like the Bayes' theorem are often used in these models.

- Binary Independence Model

- Probabilistic relevance model on which is based the okapi (BM25) relevance function

- Uncertain inference

- Language models

- Divergence-from-randomness model

- Latent Dirichlet allocation

- Feature-based retrieval models view documents as vectors of values of feature functions (or just features) and seek the best way to combine these features into a single relevance score, typically by learning to rank methods. Feature functions are arbitrary functions of document and query, and as such can easily incorporate almost any other retrieval model as just a yet another feature.

Second dimension: properties of the model[]

- Models without term-interdependencies treat different terms/words as independent. This fact is usually represented in vector space models by the orthogonality assumption of term vectors or in probabilistic models by an independency assumption for term variables.

- Models with immanent term interdependencies allow a representation of interdependencies between terms. However the degree of the interdependency between two terms is defined by the model itself. It is usually directly or indirectly derived (e.g. by dimensional reduction) from the co-occurrence of those terms in the whole set of documents.

- Models with transcendent term interdependencies allow a representation of interdependencies between terms, but they do not allege how the interdependency between two terms is defined. They relay an external source for the degree of interdependency between two terms. (For example a human or sophisticated algorithms.)

Awards in the field[]

- Tony Kent Strix award

- Gerard Salton Award

See also[]

- Automated information coding

- Automated information processing

- Automated information storage

- Communication systems

- Computer searching

- Concept mining

- Data processing

- Electronic communication

- Expert systems

- Index term

- Information

- Information extraxtion

- Information services

- Information systems

- Knowledge Organization System

- Ontology (information science)

- Ontology learning

- Semantic field

- Semantic lexicon

- Simple Knowledge Organization System

- Thesaurus

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Singhal, Amit (2001). Modern Information Retrieval: A Brief Overview. Bulletin of the IEEE Computer Society Technical Committee on Data Engineering 24 (4): 35–43.

- ↑ Mooers, Calvin N.; Theory Digital Handling Non-numerical Information (Zator Technical Bulletin No. 48) 5, cited in "information, n.". OED Online. December 2011. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Doyle, Lauren (1975). Information Retrieval and Processing, 410 pp., Melville.

- ↑ Maron, Melvin E. (2008). An Historical Note on the Origins of Probabilistic Indexing. Information Processing and Management 44 (2): 971–972.

- ↑ N. Jardine, C.J. van Rijsbergen (December 1971). The use of hierarchic clustering in information retrieval. Information Storage and Retrieval 7 (5): 217–240.

- ↑ Korfhage, Robert R. (1997). Information Storage and Retrieval, 368 pp., Wiley.

- ↑ Goodrum, Abby A. (2000). Image Information Retrieval: An Overview of Current Research. Informing Science 3.

- ↑ Foote, Jonathan (1999). An overview of audio information retrieval. Multimedia Systems.

- ↑ Beel, Jöran (2009). Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing (CollaborateCom'09).

- ↑ Frakes, William B. (1992). Information Retrieval Data Structures & Algorithms, Prentice-Hall, Inc..

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Zhu, Mu (2004). {{{title}}}.

- ↑ Turpin, Andrew (2006). User performance versus precision measures for simple search tasks. Proceedings of the 29th Annual international ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in information Retrieval (Seattle, WA, August 06-11, 2006): 11–18.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Everingham, Mark (June 2010). The PASCAL Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge. International Journal of Computer Vision 88 (2): 303–338.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Manning, Christopher D. (2008). Introduction to Information Retrieval, Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ K.H. Brodersen, C.S. Ong, K.E. Stephan, J.M. Buhmann (2010). The binormal assumption on precision-recall curves. Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, 4263-4266.