Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Personality: Self concept · Personality testing · Theories · Mind-body problem

- This article is about humors in ancient and medieval medicine. For the modern psychological theory of temperament, see Four Temperaments.

Humorism, or humoralism, was a theory of the makeup and workings of the human body adopted by Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers. From Hippocrates onward, the humoral theory was adopted by Greek, Roman and Islamic physicians, and became the most commonly held view of the human body among European physicians until the advent of modern medical research in the nineteenth century.

The four humors[]

Essentially, this theory held that the human body was filled with four basic substances, called four humors, which are in balance when a person is healthy. All diseases and disabilities resulted from an excess or deficit of one of these four humors. The four humors were identified as black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. Greeks and Romans, and the later Muslim and Western European medical establishments that adopted and adapted classical medical philosophy, believed that each of these humors would wax and wane in the body, depending on diet and activity. When a patient was suffering from a surplus or imbalance of one fluid, then his or her personality and physical health would be affected. This theory was closely related to the theory of the four elements: earth, fire, water and air; earth predominantly present in the black bile, fire in the yellow bile, water in the phlegm, and all four elements present in the blood.[1]

Theophrastus and others developed a set of characters based on the humors. Those with too much blood were sanguine. Those with too much phlegm were phlegmatic. Those with too much yellow bile were choleric, and those with too much black bile were melancholic.

Through the neo-classical revival in Europe, the humor theory dominated medical practice, and the theory of humoral types made periodic appearances in drama. Such typically "eighteenth-century" practices as bleeding a sick person or applying hot cups to a person were, in fact, based on the humor theory of surpluses of fluids (blood and bile in those cases).

Additionally, because people believed that there were unreplenishable amounts of humors in the body, there were folk/medical beliefs that the loss of fluids was a form of death.

The four humors and blood sedimentation[]

Fahråeus (1921), a Swedish physician who devised the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, suggested that the four humours were based upon the observation of blood clotting in a transparent container. When blood is drawn in a glass container and left undisturbed for about an hour, four different layers can be seen. A dark clot forms at the bottom (the "black bile"). Above the clot is a layer of red blood cells (the "blood"). Above this is a whitish layer of white blood cells (the "phlegm", now called the buffy coat). The top layer is clear yellow serum (the "yellow bile"). [2]

History and the connection with temperament theory[]

Although modern medical science has thoroughly discredited humorism, this "wrong-headed theory dominated medical thinking... until at least the middle of the 20th century, and in certain ways continues to influence modern-day diagnosis and therapy." [3]

The concept of four humors may have origins in ancient Egypt[4] or Mesopotamia,[5] but it was not systemized until ancient Greek thinkers[6] around 400 BC who directly linked it with the popular theory of the four elements earth, fire, water and air (Empedocles). Paired qualities were associated with each humor and its season. The word humor derives from the Greek χυμός, chymos (literally juice or sap, metaphorically flavor).

The four humors, their corresponding elements, seasons, sites of formation, and resulting temperaments alongside their modern equivalents are:[7]

| Humour | Season | Element | Organ | Qualities | Ancient name | Modern | MBTI | Ancient characteristics |

| Blood | spring | air | liver | warm & moist | sanguine | artisan | SP | courageous, hopeful, amorous |

| Phlegm | winter | water | brain/lungs | cold & moist | phlegmatic | guardian | SJ | calm, unemotional |

| Yellow bile | summer | fire | gall bladder | warm & dry | choleric | idealist | NF | easily angered, bad tempered |

| Black bile | autumn | earth | spleen | cold & dry | melancholic | rationalist | NT | despondent, sleepless, irritable |

Greek medicine[]

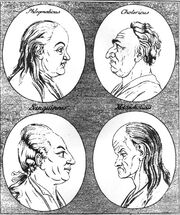

The four temperaments (Clockwise from top right: choleric; melancholic; sanguine; phlegmatic).

Hippocrates is the one usually credited with applying this idea to medicine. Humoralism, or the doctrine of the four temperaments, as a medical theory retained its popularity for centuries largely through the influence of the writings of Galen (131–201 AD) and was decisively displaced only in 1858 by Rudolf Virchow's newly published theories of cellular pathology. While Galen thought that humors were formed in the body, rather than ingested, he believed that different foods had varying potential to be acted upon by the body to produce different humors. Warm foods, for example, tended to produce yellow bile, while cold foods tended to produce phlegm. Seasons of the year, periods of life, geographic regions and occupations also influenced the nature of the humors formed.

The imbalance of humors, or dyscrasia, was thought to be the direct cause of all diseases. Health was associated with a balance of humors, or eucrasia. The qualities of the humors, in turn, influenced the nature of the diseases they caused. Yellow bile caused warm diseases and phlegm caused cold diseases.

In On the Temperaments, Galen further emphasized the importance of the qualities. An ideal temperament involved a balanced mixture of the four qualities. Galen identified four temperaments in which one of the qualities, warm, cold, moist or dry, predominated and four more in which a combination of two, warm and moist, warm and dry, cold and dry or cold and moist, dominated. These last four, named for the humors with which they were associated—that is, sanguine, choleric, melancholic and phlegmatic, eventually became better known than the others. While the term temperament came to refer just to psychological dispositions, Galen used it to refer to bodily dispositions, which determined a person's susceptibility to particular diseases as well as behavioral and emotional inclinations.

Islamic medicine[]

- See also: Medicine in medieval Islam and Unani

In Islamic medicine, Avicenna (980–1037) supported the ancient theory of four humours in The Canon of Medicine (1025), but refined in various ways. In disease pathogenesis, for example, Avicenna "added his own view of different types of spirits (or vital life essences) and souls, whose disturbances might lead to bodily diseases because of a close association between them and such master organs as the brain and heart. An element of such belief is apparent in the chapter of al-Lawa" which relates "the manifestations to an interruption of vital life essence to the brain." He combined his own view with that of the Four Humours to establish a new doctrine to explain the mechanisms of various diseases in his Treatise on Pulse:[8]

“From mixture of the four [humors] in different weights, [God the most high] created different organs; one with more blood like muscle, one with more black bile like bone, one with more phlegm like brain, and one with more yellow bile like lung.

[God the most high] created the souls from the softness of humors; each soul has it own weight and amalgamation. The generation and nourishment of proper soul takes place in the heart; it resides in the heart and arteries, and is transmitted from the heart to the organs through the arteries. At first, it [proper soul] enters the master organs such as the brain, liver or reproductive organs; from there it goes to other organs while the nature of the soul is being modified in each [of them]. As long as [the soul] is in the heart, it is quite warm, with the nature of fire, and the softness of bile is dominant. Then, that part which goes to the brain to keep it vital and functioning, becomes colder and wetter, and in its composition the serous softness and phlegm vapor dominate. That part, which enters the liver to keep its vitality and functions, becomes softer, warmer and sensibly wet, and in its composition the softness of air and vapor of blood dominate.

In general, there are four types of proper spirit: One is brutal spirit residing in the heart and it is the origin of all spirits. Another – as physicians refer to it – is sensual spirit residing in the brain. The third – as physicians refer to it – is natural spirit residing in the liver. The fourth is generative – i.e. procreative – spirits residing in the gonads. These four spirits go-between the soul of absolute purity and the body of absolute impurity.”

He also extended the theory of temperaments in The Canon of Medicine to encompass "emotional aspects, mental capacity, moral attitudes, self-awareness, movements and dreams." He summarized his version of the four humors and temperaments in a table as follows:[9]

| Evidence | Hot | Cold | Moist | Dry |

| Morbid states | inflammations become febrile | fevers related to serious humor, rheumatism | lassitude | loss of vigour |

| Functional power | deficient energy | deficient digestive power | difficult digestion | |

| Subjective sensations | bitter taste, excessive thirst, burning at cardia | Lack of desire for fluids | mucoid salivation, sleepiness | insomnia, wakefulness |

| Physical signs | high pulse rate, lassitude | flaccid joints | diarrhea, swollen eyelids, rough skin, acquired habit | rough skin, acquired habit |

| Foods & medicines | calefacients harmful, infrigidants beneficial | infrigidants harmful, calefacients beneficial | moist articles harmful | dry regimen harmful, humectants beneficial |

| Relation to weather | worse in summer | worse in winter | bad in autumn | |

Rhazes (865–925) was the first physician to refute the theory of four humors in his Doubts about Galen. He carried out an experiment which would upset this system by inserting a liquid with a different temperature into the body resulting in an increase or decrease of bodily heat, which resembled the temperature of that particular fluid. Rhazes noted that a warm drink would heat up the body to a degree much higher than its own natural temperature, thus the drink would trigger a response from the body, rather than transferring only its own warmth or coldness to it.[10] Avenzoar (1091–1161) carried out an experimental dissection and autopsy to prove that the skin disease scabies was caused by a parasite, a discovery which upset the theory of humorism. The removal of the parasite from the patient's body did not involve purging, bloodletting, or any other traditional treatments associated with the four humors.[11] Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) then discredited the theory of four humors after his discovery of pulmonary circulation[12] and coronary circulation.[13]

Influence and legacy[]

Methods of treatment like bloodletting, emetics and purges were aimed at expelling a harmful surplus of a humor. Other methods used herbs and foods associated with a particular humor to counter symptoms of disease, for instance: people who had a fever and were sweating were considered hot and wet and therefore given substances associated with cold and dry. Paracelsus further developed the idea that beneficial medical substances could be found in herbs, minerals and various alchymical combinations thereof. These beliefs were the foundation of mainstream Western medicine well into the 1800s.

There are still remnants of the theory of the four humors in the current medical language. For example, we refer to humoral immunity or humoral regulation to mean substances like hormones and antibodies that are circulated throughout the body, or use the term blood dyscrasia to refer to any blood disease or abnormality. The associated food classification survives in adjectives that are still used for food, as when we call some spices "hot" and some wine "dry". When the chilli pepper was first introduced to Europe in the sixteenth century, dieticians disputed whether it was hot or cold.

Foods in Elizabethan times were believed all to have an affinity with one of these four humors. A person suffering from a sickness in which they were coughing up phlegm were believed to be too phlegmatic and might have been served wine (a choleric drink and the direct opposite humor to phlegmatic) to balance it out.

The theory was an advance toward modern views of human health over the previous views that tried to explain disease in terms of evil spirits. Since then, practitioners have started to look for biological causes of disease and to provide biological treatments.

The Unani school of Indian medicine, still apparently practiced in India, is very similar to Galenic and Avicennian medicine in its emphasis on the four humors and in treatments based on controlling intake, general environment, and the use of purging as a way of relieving humoral imbalances.

See also[]

- Three Doshas of Ayurveda

- Four Temperaments

- Five Temperaments

- Wu Xing (Five Elements of Chinese philosophy)

References[]

- ↑ Wittendorff, Alex (1994). Tyge Brahe, G.E.C. Gad. p45

- ↑ DESCRIPTIONS OF BLOOD AND BLOOD DISORDERS BEFORE THE ADVENT OF LABORATORY STUDIES by Holmead Walk and Gerald D. Hart, British Journal of Haematology, 2001, 115, 719-728

- ↑ NY Times Book Review Bad Medicine

- ↑ van Sertima, Ivan (1992), The Golden Age of the Moor, Transaction Publishers, p. 17, ISBN 1560005815

- ↑ Sudhoff, Karl (1926), Essays in the History of Medicine, Medical Life Press, New York, pp. 67, 87, 104

- ↑ Hippocrates (ca. 460 BC – ca. 370 BC): in Hippocratic Corpus, On The Sacred Disease.

- ↑ Keirsey, David (1998). Please Understand Me II: Temperament, Character, Intelligence, 26, Del Mar, CA: Prometheus Nemesis Book Company.

- ↑ Mohammadali M. Shojaa, R. Shane Tubbsb, Marios Loukasc, Majid Khalilid, Farid Alakbarlie, Aaron A. Cohen-Gadola (29 May 2009), "Vasovagal syncope in the Canon of Avicenna: The first mention of carotid artery hypersensitivity", International Journal of Cardiology (Elsevier) 134 (3): 297-301, doi:

- ↑ Lutz, Peter L. (2002), The Rise of Experimental Biology: An Illustrated History, Humana Press, p. 60, ISBN 0896038351

- ↑ G. Stolyarov II (2002), "Rhazes: The Thinking Western Physician", The Rational Argumentator, Issue VI.

- ↑ Islamic medicine, Hutchinson Encyclopedia.

- ↑ S. A. Al-Dabbagh (1978). "Ibn Al-Nafis and the pulmonary circulation", The Lancet 1, p. 1148.

- ↑ Husain F. Nagamia (2003), "Ibn al-Nafīs: A Biographical Sketch of the Discoverer of Pulmonary and Coronary Circulation", Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine 1, p. 22–28.

External links[]

- In Our Time (BBC Radio 4) episode on the four humors in MP3 format, 45 minutes

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |