Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Biological: Behavioural genetics · Evolutionary psychology · Neuroanatomy · Neurochemistry · Neuroendocrinology · Neuroscience · Psychoneuroimmunology · Physiological Psychology · Psychopharmacology (Index, Outline)

|

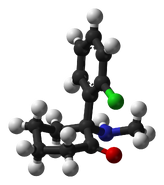

Ketamine chemical structure | |

| 2-(2-chlorophenyl)- 2-methylamino- cyclohexan- 1-one IUPAC name | |

| CAS number 6740-88-1 |

ATC code N01AX03 . |

| PubChem 3821 |

DrugBank APRD00493 |

| Chemical formula | {{{chemical_formula}}} |

| Molecular weight | 237.725 g/mol |

| Bioavailability | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, primarily by CYP3A4[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5-3 hours. |

| Excretion | renal (>90%) |

| Pregnancy category | B |

| Legal status | |

| Routes of administration | IV, IM, Insufflated, oral, topical |

Ketamine is a drug used in human and veterinary medicine developed by Parke-Davis (today a part of Pfizer) in 1962. Its hydrochloride salt is sold as Ketanest, Ketaset, and Ketalar. Pharmacologically, ketamine is classified as an NMDA receptor antagonist[2]. At high, fully anesthetic level doses, ketamine has also been found to bind to opioid μ receptors and sigma receptors. [How to reference and link to summary or text] Like other drugs of this class such as tiletamine and phencyclidine (PCP), it induces a state referred to as "dissociative anesthesia"[3] and is used as a recreational drug.

Ketamine has a wide range of effects in humans, including analgesia, anesthesia, hallucinations, elevated blood pressure, and bronchodilation.[How to reference and link to summary or text] Ketamine is primarily used for the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia, usually in combination with some sedative drug. Other uses include sedation in intensive care, analgesia (particularly in emergency medicine), and treatment of bronchospasm. It is also a popular anesthetic in veterinary medicine.

Ketamine is a chiral compound. Most pharmaceutical preparations of ketamine are racemic; however, some brands reportedly have (mostly undocumented) differences in enantiomeric proportions. The more active enantiomer, S-ketamine, is also available for medical use under the brand name Ketanest S.[4] Ketamine is a core medicine in the World Health Organization's "Essential Drugs List", which is a list of minimum medical needs for a basic health care system.[5]

History[]

Ketamine was developed by Dr. Craig Newlands of Wayne State University. It was then developed by Parke-Davis in 1962 as part of an effort to find a safer anesthetic alternative to phencyclidine (PCP), which was more likely to cause hallucinations, neurotoxicity and seizures. The drug was first given to American soldiers during the Vietnam War. It is still widely used in humans. There may be some evidence that ketamine has the potential to cause emergence phenomena because of the drug's possible psychotomimetic effects.[How to reference and link to summary or text] It is also used widely in veterinary medicine, or as a battlefield anesthetic in developing nations.[6]

Ketamine's side effects eventually made it a popular dissociative in 1965. The drug was used in psychiatric and other academic research through the 1970s, culminating in 1978 with the publishing of John Lilly's The Scientist and Marcia Moore and Howard Alltounian's Journeys into the Bright World, which documented the unusual phenomenology of ketamine intoxication.[7]

The incidence of recreational ketamine use increased through the end of the century, especially in the context of raves and other parties. The increase in illicit use prompted ketamine's placement in Schedule III of the United States Controlled Substance Act in August 1999.[8] In the United Kingdom, it became outlawed and labeled a Class C drug on January 1, 2006.[9] In Canada ketamine is classified as a Schedule I narcotic, as of August 2005.[10] In Hong Kong, as of year 2000, ketamine is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. It can only be used legally by health professionals, for university research purposes, or with a physician's prescription.[11]

Medical use[]

10ml bottles of ketamine (veterinary use)

- Sight

- Balance

- Sense of time

- Partial depressant

Musculoskeletal:

- Partial depressant/stimulant

Contraindications:

|

In medical settings, ketamine is usually injected intravenously or intramuscularly,[12] but it is also effective when insufflated, smoked, or taken orally.[13]

Since it suppresses breathing much less than most other available anaesthetics,[14] ketamine is still used in human medicine as an anesthetic, however, due to the hallucinations which may be caused by ketamine, it is not typically used as a primary anesthetic, although it is the anaesthetic of choice when reliable ventilation equipment is not available. Ketamine tends to increase heart rate and blood pressure. Because ketamine tends to increase or maintain cardiac output, it is sometimes used in anesthesia for emergency surgery when the patient's state of fluid volume status is unknown (e.g., from traffic accidents). Ketamine can be used in podiatry and other minor surgery, and occasionally for the treatment of migraine. There is ongoing research in France, the Netherlands, Russia, Australia and the U.S. into the drug's usefulness in pain therapy, depression suppression, and for the treatment of alcoholism[15] and heroin addiction.[16]

In veterinary anesthesia, ketamine is often used for its anesthetic and analgesic effects on cats, dogs, rabbits, rats, and other small animals. Veterinarians often use ketamine with sedative drugs to produce balanced anesthesia and analgesia, and as a constant rate infusion to help prevent pain wind-up. Ketamine is used to manage pain among large animals, though it has less effect on bovines. It is the primary intravenous anesthetic agent used in equine surgery, often in conjunction with detomidine and thiopental, or sometimes guaifenesin.

Ketamine may be used in small doses (0.1–0.5 mg/kg/h) as a local anesthetic, particularly for the treatment of pain associated with movement and neuropathic pain.[17] It may also be used as an intravenous co-analgesic together with opiates to manage otherwise intractable pain, particularly if this pain is neuropathic (pain due to vascular insufficiency or shingles are good examples). It has the added benefit of counter-acting spinal sensitization or wind-up phenomena experienced with chronic pain. At these doses, the psychotropic side effects are less apparent and well managed with benzodiazepines.[18] Ketamine is a co-analgesic, and so is most effective when used alongside a low-dose opioid; while it does have analgesic effects by itself, the higher doses required can cause disorienting side effects.[18] The combination of ketamine with an opioid is, however, particularly useful for pain caused by cancer.[19]

The effect of ketamine on the respiratory and circulatory systems is different from that of other anesthetics. When used at anesthetic doses, it will usually stimulate rather than depress the circulatory system.[20] It is sometimes possible to perform ketamine anesthesia without protective measures to the airways. Ketamine is also a potent analgesic and can be used in sub-anesthetic doses to relieve acute pain; however, its psychotropic properties must be taken into account. Patients have reported vivid hallucinations, "going into other worlds" or "seeing God" while anesthetized, and these unwanted psychological side-effects have reduced the use of ketamine in human medicine. They can, however, usually be avoided by concomitant application of a sedative such as a benzodiazepine.[18]

Low-dose ketamine is recognized for its potential effectiveness in the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), according to a retrospective review published in the October 2004 issue of Pain Medicine.[21] Although low-dose ketamine therapy is established as a generally safe procedure, reported side effects in some patients have included hallucinations, dizziness, lightheadedness and nausea. Therefore nurses administering ketamine to patients with CRPS should only do so in a setting where a trained physician is available if needed to assess potential adverse effects on patients.[22]

Experimental antidepressant use[]

100 g of Ketamine Template:Deletable image-caption

When treating patients suffering from complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) with a low-dose (subanesthetic) ketamine infusion, it was observed that some patients made a significant recovery from associated depression. This recovery was not formally documented, as the primary concern was the treatment of the patient's pain. It was not possible to quantify to what degree depression recovery was secondary to the patient's recovery from CRPS. Based on this result, it was thought that a low-dose (subanesthetic) infusion of ketamine was worth a trial in patients who were suffering from treatment-resistant depression without other physical or psychiatric illness.

Correll, et al. gave ketamine intravenously to patients commencing at 15–20 mg/h (0.1–0.2 mg/kg/h) and the dose increased until a maximum tolerated dose was achieved. This dose was assumed to be a therapeutic dose and was maintained for 5 days. Patients were able to eat, drink, watch television, or read. They could feel inebriated and/or unsteady when walking. If hallucinations occurred, the dose was to be reduced. The patients' normal medications were continued as it was feared that stopping them might result in severe depressive episodes. Before and following each treatment with ketamine, at patient clinic visits, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17) were obtained. Two of the patients were described with "impressive", as described by an attending doctor, improvement in depression being maintained for 12 months in patient A and recurrence at 2.5 months and 9 months in patient B.[23]

The National Institute of Health News reports that a study of 18 patients has found that ketamine significantly improved treatment-resistant major depression within hours of injection.[24] The improvement lasted up to one week after the single dose.[25] The patients in the study were previously treatment resistant, having tried an average of six other treatments that failed. NIMH director Dr. Thomas Insel said in the paper:

"To my knowledge, this is the first report of any medication or other treatment that results in such a pronounced, rapid, prolonged response with a single dose. These were very treatment-resistant patients."

The researchers apparently attribute the effect to ketamine being an NMDA receptor antagonist.[26] Those findings of Zarate et al. corroborate earlier findings by Berman et al..[27] However Zarate et al. do raise some concerns about their results due to a possible lack of blinding, because of the inebriating effects of low dose ketamine infusion, and it is recommended that future studies include an active placebo.

The findings by Zarate et al. are confirmed by Liebrenz et al., who substantially, according to an attending doctor, helped a 55-year-old male subject with a treatment-resistant major depression and a co-occurring alcohol and benzodiazepine dependence by giving an intravenous infusion of 0.5 mg/kg ketamine over a period of 50 minutes and Goforth et al. who helped a patient with severe, recurrent major depressive disorder that demonstrated marked improvement within 8 hours of receiving a preoperative dose of ketamine and one treatment of electroconvulsive therapy with bitemporal electrode placement.[28]<[29]

However, a new study in mice by Zarate et al. shows that blocking the NMDA receptor is an intermediate step. According to this study, blocking NMDA increases the activity of another receptor, AMPA, and this boost in AMPA activity is crucial for ketamine’s rapid antidepressant actions. NMDA and AMPA are receptors for the neurotransmitter glutamate. The glutamate system has been implicated in depression recently. This is a departure from previous thinking, which had focused on serotonin and norepinephrine. The glutamate system may represent a new avenue for treatment and research.[30]

Krystal et al. retrospectively compared the seizure duration, ictal EEG, and cognitive side effects of ketamine and methohexital anesthesia with ECT in 36 patients.[31] Ketamine was well tolerated and prolonged seizure duration overall, but particularly in those who had a seizure duration shorter than 25 seconds with methohexital at the maximum available stimulus intensity. Ketamine also increased midictal EEG slow-wave amplitude. Thus, a switch to ketamine may be useful when it is difficult to elicit a robust seizure. Faster post-treatment reorientation with ketamine may suggest a lower level of associated cognitive side effects.

Kudoh et al. investigated whether ketamine is suitable for depressed patients who had undergone orthopedic surgery.[32] They studied 70 patients with major depression and 25 patients as the control (Group C). The depressed patients were divided randomly into two groups; patients in Group A, initial HAMD 12,7 (n = 35) were induced with propofol, fentanyl, and ketamine and patients in Group B, initial HAMD 12,3 (n = 35) were induced with propofol and fentanyl. Depressed mood, suicidal tendencies, somatic anxiety, and hypochondriasis significantly decreased in Group A as compared with Group B. The group receiving ketamine also had significantly lower postoperative pain.

Acute administration of ketamine at the higher dose, but not imipramine, increased BDNF protein levels in the rat hippocampus. The increase of hippocampal BDNF protein levels induced by ketamine might be necessary to produce a rapid onset of antidepressant action.[33]

Treatment of addiction[]

The Russian doctor Evgeny Krupitsky (Clinical Director of Research for the Saint Petersburg Regional Center for Research in Addiction and Psychopharmacology) has claimed to have encouraging results by using ketamine as part of a treatment for alcohol addiction which combines psychedelic and aversive techniques.[34][35] This method involved psychotherapy, controlled ketamine use and group therapy, and resulted in 60 of the 86 alcoholic males selected for the study remaining fully abstinent through one year of treatment. He has also treated heroin addicts and reached the conclusion that one ketamine-assisted psychotherapy session was significantly more effective than active placebo in promoting abstinence from heroin during one year without any adverse reactions. In a recently published study 59 detoxified inpatients with heroin dependence received a ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KPT) session prior to their discharge from an addiction treatment hospital, and were then randomized into two treatment groups.

Participants in the first group received two addiction counseling sessions followed by two KPT sessions, (with a single im injection of 2 mg/kg ketamine) with sessions scheduled on a monthly interval (multiple KPT group). Participants in the second group received two addiction counseling sessions on a monthly interval, but no additional ketamine therapy sessions (single KPT group). At one-year follow-up, survival analysis demonstrated a significantly higher rate of abstinence in the multiple KPT group. Thirteen out of 26 subjects (50%) in the multiple KPT group remained abstinent, compared to 6 out of 27 subjects (22.2%) in the single KPT group (p < 0.05). No differences between groups were found in depression, anxiety, craving for heroin, or their understanding of the meaning of their lives. It was concluded that three sessions of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy are more effective than a single session for the treatment of heroin addiction.[36][37]

In a 2007 chapter "Ketamine Psychedelic Psychotherapy" Krupitsky and Kolp summarize their work-to-date in Chapter 5 in Psychedelic Medicine: New Evidence for Hallucinogens as Treatments,[38]

Jovaisa et al. from Lithuania demonstrated attenuation of opiate withdrawal symptoms with ketamine. A total of 58 opiate-dependent patients were enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Patients underwent rapid opiate antagonist induction under general anesthesia. Prior to opiate antagonist induction patients were given either placebo (normal saline) or subanesthetic ketamine infusion of 0.5 mg/kg/h. Ketamine group presented better control of withdrawal symptoms, which lasted beyond ketamine infusion itself. Significant differences between ketamine and Control groups were noted in anesthetic and early postanesthetic phases. There were no differences in effects on outcome after 4 months.[16]

Treatment of reflex sympathetic dystrophy[]

Ketamine is being used as an experimental and controversial treatment for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) also known as Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (RSD). CRPS/RSD is a severe chronic pain condition characterized by sensory, autonomic, motor and dystrophic signs and symptoms. The pain in CRPS is continuous, it worsens over time, and it is usually disproportionate to the severity and duration of the inciting event. The hypothesis is that ketamine manipulates NMDA receptors which might reboot aberrant brain activity. There are two treatment modalities, the first consist of a low dose ketamine infusion of between 25-90 mg per day, over five days either in hospital or as an outpatient. This is called the awake technique. Open label, prospective, pain journal evaluation of a 10-day infusion of intravenous ketamine (awake technique) in the CRPS patient concluded that "A four-hour ketamine infusion escalated from 40-80 mg over a 10-day period can result in a significant reduction of pain with increased mobility and a tendency to decreased autonomic dysregulation".[39]

Case notes of 33 patients whose CRPS pain was treated by the inpatient administration of a continuous subanesthetic intravenous infusion of ketamine were reviewed at Mackay Base Hospital, Queensland, Australia. A total of 33 patients with diagnoses of CRPS who had undergone ketamine treatment at least once were identified. Due to relapse, 12 of 33 patients received a second course of therapy, and two of 33 patients received a third. There was complete pain relief in 25 (76%), partial relief in six (18%), and no relief in two (6%) patients.

The degree of relief obtained following repeat therapy (N=12) appeared even better, as all 12 patients who received second courses of treatment experienced complete relief of their CRPS pain. The duration of relief was also impressive, as was the difference between the duration of relief obtained after the first and after the second courses of therapy. In this respect, following the first course of therapy, 54% of 33 individuals remained pain free for >/=3 months and 31% remained pain free for >/=6 months. After the second infusion, 58% of 12 patients experienced relief for >/=1 year, while almost 33% remained pain free for >3 years. The most frequent side effect observed in patients receiving this treatment was a feeling of inebriation. Hallucinations occurred in six patients. Less frequent side effects also included complaints of light-headedness, dizziness, and nausea. In four patients, an alteration in hepatic enzyme profile was noted; the infusion was terminated and the abnormality resolved thereafter. No long-term side-effects were noted.[40]

The second treatment modality consists of putting the patient into a medically-induced coma and given an extremely high dosage of ketamine; typically between 600-900 mg.[41] This version, currently not allowed in the United States, is most commonly done in Germany but some treatments are now also taking place in Monterrey, Mexico. According to Dr Schwartzman, 14 cases out of 41 patients in the coma induced ketamine experiments were completely cured. "We haven't cured the original injury," he says, "but we have cured the RSD or kept it in remission. The RSD pain is gone." He added that "No one ever cured it before... In 40 years, I have never seen anything like it. These are people who were disabled and in horrible pain. Most were completely incapacitated. They go back to work, back to school, and are doing everything they used to do. Most are on no medications at all. I have taken morphine pumps out of people. You turn off the pain and reset the whole system."[41]

In Tuebingen, Germany Dr Kiefer treated a patient presented with a rapidly progressing contiguous spread of CRPS from a severe ligamentous wrist injury. Standard pharmacological and interventional therapy successively failed to halt the spread of CRPS from the wrist to the entire right arm. Her pain was unmanageable with all standard therapy. As a last treatment option, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and treated on a compassionate care basis with anesthetic doses of ketamine in gradually increasing (3-5 mg/kg/h) doses in conjunction with midazolam over a period of 5 days. On the second day, edema, and discoloration began to resolve and increased spontaneous movement was noted. On day 6, symptoms completely resolved and infusions were tapered. The patient emerged from anesthesia completely free of pain and associated CRPS signs and symptoms. The patient has maintained this complete remission from CRPS for 8 years now. The psychiatric side effects of ketamine were successfully managed with the concomitant use of midazolam and resolved within 1 month of treatment.[42]

Postoperative pain[]

The dissociative anesthetic effects of ketamine have also been applied within the realm of postoperative pain management. Low doses of ketamine have been found to significantly reduce morphine consumption as well as reports of nausea following abdominal surgery.[43]

Contents of various brands of ketamine[]

Ketanest S Parke Davis (Pfizer) - S enantiomer only, no preservatives[44]

Ketaset® (Wyeth) - R/S ketamine and benzethonium chloride as a preservative.[45]

Ketanest - S ketamine only

Ketalar - D/L ketamine + Phermerol® (benzethonium chloride) added as a preservative

Neuropharmacology[]

Ketamine was long thought to act primarily by inhibiting NMDA receptors (see below). But another NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801, does not exert the same hypnotic effects[46]. It appears more likely that the hypnotic effects of ketamine are produced by inhibiting hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-modulated (HCN1) cation channels, which mediate the "sag" current (Ih ) in neurons. Inhibition of Ih by ketamine in cultured neurons causes a hyperpolarizing shift in resting membrane potential and enhances summation of excitatory currents[47]. Such effects, if induced in vivo, would likely induce cortical oscillations reminiscent of sleep[48]. Most importantly, knockout of HCN1 channels in mice eliminates the hypnotic actions of ketamine[49].

Ketamine, like phencyclidine, is also a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist[2]. This receptor opens in response to binding of the neurotransmitter glutamate, and mediates the analgesic (reduction of pain) effects of ketamine at low doses. [How to reference and link to summary or text] Evidence for this is reinforced by the fact that naloxone, an opioid antagonist, does not reverse the analgesia. Studies also seem to indicate that ketamine is "use dependent" meaning it only initiates its blocking action once a glutamate binds to the NMDA receptor.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

At high, fully anesthetic level doses, ketamine has also been found to bind to opioid mu receptors and sigma receptors.[How to reference and link to summary or text] Thus, loss of consciousness that occurs at high doses may be partially due to binding at the opioid mu and sigma receptors.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

(rac)-ketamine is a noncompetitive inhibitor of the α7 nAChR at clinically relevant concentrations. The preservative benzethonium chloride competitively inhibits α7 and α4β2 nAChRs at concentrations present in the clinical formulation of Ketalar.[50]

Ketamine is racemic, and its R and S stereoisomers have different binding affinities: (S)-ketamine has about four times greater affinity for the PCP site of the NMDA receptor than does (R)-ketamine (in guinea pig brain).[How to reference and link to summary or text] (S)-ketamine seems to induce drowsiness more strongly than the (R) enantiomer; it is probable that (R)-ketamine is the stronger sigma agonist and so this enantiomer is likely to be responsible for the lowering of the seizure threshold that can occur with ketamine.[How to reference and link to summary or text] Since (S)-ketamine has greater analgesic effects and less hallucinogenic side effects than (R)-ketamine, the pure (S) enantiomer is sometimes preferred to the racemic mix for use in medical procedures, especially when lower doses are used for minor surgical procedures where the patient remains conscious during the operation.[51]

The effects seem to take place mainly in the hippocampal formation and in the prefrontal cortex. This evidence, along with the NMDA receptor's connection with the memory formation process, explains ketamine's profound effects on memory and thought. These effects inhibit the filtering function of the brain and may mirror the sensory overload associated with schizophrenia and near death experiences.[How to reference and link to summary or text]

The local anesthetic effects are likely from the blocking action of ketamine on sodium channels.[52] Its in vitro blocking potency of sodium channels in the resting state is similar to that of lidocaine.[53]

Ketamine has a well-documented neuroprotective effect against ischemic brain-injury and glutamate induced brain injury.[54] One hypothesis of its working mechanism in case of chronic pain management and depression is that it works as an antidote to an overactivity in glutamergic brain circuits.

Recreational use[]

Illicit sale[]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2008) |

10 ml bottle of liquid ketamine drying into crystals

500mg Ketamine Hydrochloride

Ketamine dried and scraped

Ketamine sold illicitly comes from diverted legitimate supplies and semi-legitimate suppliers, or theft, primarily from veterinary clinics. Most of the world's illicit ketamine comes from Asia-based pharmaceutical manufacturers, who often willingly sell it to Western individuals, who then sell it to users. This way, many ounces or even kilos of pharmaceutical ketamine are sold and shipped in each transaction by legitimate Asian producers, who will sometimes relabel the packaging before shipping with names of unregulated chemicals, making it harder for customs to discover the shipments. The many commercial advertisement websites aimed at companies who are looking to import or export products has made it a lot easier for individuals to buy ketamine over the Internet. Until recent years ketamine wasn't regulated in most countries, and customs and police authorities were powerless to stop the import of bulk pharmaceutical ketamine from Asian manufacturers; though this has changed due to the rising number of reports of use/abuse of ketamine, prompting countries to regulate the drug. Chinese authorities tried to regulate the production and sale of ketamine more as well in recent years, and several large quantities of ketamine meant for illicit sale were seized by authorities. In the US near its border with Mexico, the drug is most commonly acquired in Mexico, where it can be bought over the counter in veterinary clinics, and smuggled across the border.

In 2003, Operation TKO[55] was a probe conducted by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). As a result of operation TKO, U.S. and Mexican authorities shut down the Mexico City company Laboratorios Ttokkyo, which was the biggest producer of ketamine in Mexico. According to the DEA, over 80% of ketamine seized in the U.S. is of Mexican origin.[How to reference and link to summary or text] The World Health Organization Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, in its thirty-third report (2003)[56], recommended research into its recreational use/misuse due to growing concerns about its rising popularity in Europe, Asia and North America. This is due in part to its prevention of depression.[57]

In E for Ecstasy[58] (a book examining the uses of the street drug Ecstasy in the UK) the writer, activist and Ecstasy advocate Nicholas Saunders highlighted test results showing that certain consignments of the drug also contained ketamine. Consignments of Ecstasy known as "Strawberry" contained what Saunders described as a "potentially dangerous combination of ketamine, ephedrine and selegiline," as did a consignment of "Sitting Duck" Ecstasy tablets.[59]

Methods of use[]

Ketamine is sold in either powdered or liquid form. In powdered form, its appearance is similar to that of cocaine and it can be insufflated, injected, or placed in beverages. It is also possible to smoke the drug in a joint or pipe, usually mixed with marijuana and tobacco. The smoke has a distinctive bitter taste but the effects of the high hit much faster than when insufflated, ingested or injected intramuscularly. Oral use usually requires more material, but results in a longer trip. However, when administered orally, ketamine is rapidly metabolised to norketamine, which possesses sedating effects; this route of administration is unlikely to produce a dissociative state characteristic of ketamine unless very high doses (500 mg+) are ingested. [60] Intravenous self-injection of ketamine is very dangerous.

Psychological effects[]

Ketamine produces effects similar to PCP and DXM. Unlike the other well known dissociatives PCP and DXM, ketamine is very short acting, its hallucinatory effects lasting sixty minutes when insufflated or injected and up to an two hours when ingested, the total experience lasting no more than a couple of hours. [61] Like other dissociative anaesthetics, hallucinations caused by ketamine are fundamentally different from those caused by tryptamines and phenethylamines. At low doses, hallucinations are only seen when one is in a dark room with one's eyes closed, while at medium to high doses the effects are far more intense and obvious. [62]

Ketamine produces a dissociative state, characterised by a sense of detachment from one's physical body and the external world which is known as depersonalization and derealization.[63] At sufficiently high doses (e.g. 150 mg intramuscular), users may experience what is coined the "K-hole", a state of dissociation whose effects are thought to mimic the phenomenology of schizophrenia.[64]. Users may experience worlds or dimensions that are ineffable, all the while being completely unaware of their individual identities or the external world. Users have reported intense hallucinations including visual hallucinations, perceptions of falling, fast and gradual movement and flying, 'seeing God', feeling connected to other users, objects and the cosmos, experiencing psychic connections, and shared hallucinations and thoughts with adjacent users.

Users may feel as though their perceptions are located so deep inside the mind that the real world seems distant (hence the use of a "hole" to describe the experience). Some users may not remember this part of the experience after regaining consciousness, in the same way that a person may forget a dream. Owing to the role of the NMDA receptor in long-term potentiation, this may be due to disturbances in memory formation. The "re-integration" process is slow, and the user gradually becomes aware of surroundings. At first, users may not remember their own names, or even know that they are human, or what that means. Movement is extremely difficult, and a user may not be aware that he or she has a body at all.

Long-term side effects[]

- Main article: Olney's lesions

In 1989, psychiatry professor John Olney reported that ketamine caused reversible changes in two small areas of the rat brain. 40 mg/kg resulted in fluid-filled cavities ("vacuoles") appearing inside cells. The cavities disappeared after several days, unless high doses of the far more toxic PCP or close relative MK801 were repeatedly given, in which case some cell death was seen. Roland Auer injected monkeys with MK801 and was unable to produce any vacuoles. When Auer was asked in 1998 whether persons undergoing anesthesia with Ketalar were at risk of these changes, his reply was that he doubted that it was even a remote possibility because of fundamental differences in metabolism between the rat and human brain. Ketamine can block excitotoxicity (brain damage due to low oxygen, low sugar, epilepsy, trauma, etc) but it can also excite the brain at low doses by switching off the inhibitory system. Why this isn't damaging in monkeys and humans probably lies in the fact that ketamine binds to an increasingly wide range of different receptors as the dose level rises, and some of these receptors act to shut down the excitement. In humans, by the time a potentially toxic dose is reached, the "excitement window" has been passed and the drug is starting to activate other systems that switch cells off again, a result of ketamine's promiscuity that improves its safety relative to MK801. MK801 binds very specifically to N-P receptors. The other part of the explanation is that rats have rates of brain metabolism that are almost twice as high as those in humans to start with. It is because of this higher base rate of metabolism that ketamine causes over-excitement in rats at doses below those at which it activates shutdown systems.”[65][66][67]

Vutskits et al. from Geneva showed that short-term exposure of cultures to ketamine at concentrations of ≥ 20 μg/mL leads to a significant loss of differentiated cells and that non-cell death-inducing concentrations of ketamine (10 μg/mL) can still initiate long-term alterations of dendritic arbor in differentiated neurons, including dendritic retraction and branching point elimination. They also demonstrated that chronic (>24 h) administration of ketamine at concentrations as low as 0.01 μg/mL can interfere with the maintenance of dendritic arbor architecture. These results raise the possibility that chronic exposure to low, subanesthetic concentrations of ketamine, while not affecting cell survival, could still impair neuronal morphology and thus might lead to dysfunctions of neural networks.[68]

There is a long list of medicines that could counteract these potential toxic effects, including clonidine, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, barbiturates and risperidone.[66][67] [69]

A study in Bristol reported in the British Medical Journal on 3 May 2008 linked urinary tract disease with ketamine use. Symptoms reported by users include an increased need to urinate, passing blood in urine, leakage of urine and pain on urination. These symptoms are associated with the scarification of the bladder lining, which leads to a shrunken bladder, erythema, and contact bleeding, and can then move to the ureters and damage the kidneys. [70] [How to reference and link to summary or text] In a study of 9 daily ketamine users, Shahani et al. found "marked thickening of the bladder wall, a small capacity, and perivesicular stranding, consistent with severe inflammation. At cystoscopy, all patients had severe ulcerative cystitis. Biopsies in 4 patients revealed epithelial denudation and inflammation with a mild eosinophilic infiltrate. Cessation of ketamine use, with the addition of pentosan polysulfate, appeared to provide some symptomatic relief."[71][How to reference and link to summary or text]

Many long term users report "K-Pains" or "Ketamine cramps" the exact cause of these are unknown but with extended use users report extreme pain in their lower abdomen. Heavy users report a rapid increase in tolerance.

Pop culture[]

Referred to in the song "Special K" by Placebo; "K-Hole" by Cocorosie; "Kids of the K-Hole" by NOFX; "Lost in the K-Hole" by The Chemical Brothers; "Dissassociative" by Marilyn Manson; "K Horse" by Head Automatica; "Pink Tarantulas" by The Blood Brothers; "Get ready for the K-hole" by Kissy Sell Out; "Plague (we need no victims) by Lola Ray; "Ketamine" by Get Back Loretta; and "K-Hole" by Silver Jews. Hallucination experiences have also been the reference to songs written by Goodnight And I Wish*, including 'A Lucid Dream', and, 'Norlington Works', a song based on a group of friends living within a factory in east London over the summer of 2008, and the effects that the drug has on the mind. Soulwax's video of E Talking also features a clubber who is on Ketemine.

K is also a drug used by the main characters throughout the novel Christlike by Emanuel Xavier and also used by Darby Crash of the band The Germs.

Ketamine is the drug used by the characters of the graphic novel "Effing Brutal".

In the Off-Broadway musical bare: a pop opera, students at a Catholic boarding school take K at a rave to "enhance" their "X experience". The effects of the drug are described in the song "Wonderland". [72]

The title character of the TV series House received an experimental Ketamine treatment that temporarily reduced the chronic pain from a leg infarction.

In the fictional TV series Bones, Ketamine was used to subdue a murder victim prior to his death in Season 1, Episode 3: 'A Boy in the Tree' (originally aired September 27, 2005).[73]

See also[]

- Psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants

- Psychoactive drug

- Dissociation

- Depersonalization

- Derealization

References[]

- ↑ Hijazi Y, Boulieu R. Contribution of CYP3A4, CYP2C9 and CYP2B6 in N-demethylation of ketamine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos 2002; 30: 853–8

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Harrison N, Simmonds M (1985). Quantitative studies on some antagonists of N-methyl D-aspartate in slices of rat cerebral cortex. Br J Pharmacol 84 (2): 381–91.

- ↑ Bergman S (1999). Ketamine: review of its pharmacology and its use in pediatric anesthesia. Anesth Prog 46 (1): 10–20.

- ↑ Kruger AD. Current aspects of using ketamine in childhood. Anaesthesiologie und Reanimation. 1998;23(3):64-71.

- ↑ (2005). WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. (PDF) World Health Organization. URL accessed on 2006-03-12.

- ↑ Bonanno F (2002). Ketamine in war/tropical surgery (a final tribute to the racemic mixture). Injury 33 (4): 323–7.

- ↑ Marcia Moore - Journeys into the Bright World

- ↑ Ketamine - Schedule III of The Controlled Substances Act (CSA). Anestesiología Mexicana en Internet. URL accessed on 2006-12-22.

- ↑ BBC NEWS | UK | Club 'horse' drug to be outlawed

- ↑ Controlled Drugs and Substances Act

- ↑ Government to tighten control on Ketamine

- ↑ Lankenau S, Sanders B, Bloom J, Hathazi D, Alarcon E, Tortu S, Clatts M (2007). First injection of ketamine among young injection drug users (IDUs) in three U.S. cities. Drug Alcohol Depend 87 (2-3): 183–93.

- ↑ Reboso Morales J, González Miranda F (1999). [Ketamine]. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 46 (3): 111–22.

- ↑ Heshmati F, Zeinali M, Noroozinia H, Abbacivash R, Mahoori A (2003). Use of ketamine in severe status asthmaticus in intensive care unit. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2 (4): 175–80.

- ↑ Krystal J, Madonick S, Perry E, Gueorguieva R, Brush L, Wray Y, Belger A, D'Souza D (2006). Potentiation of low dose ketamine effects by naltrexone: potential implications for the pharmacotherapy of alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology 31 (8): 1793–800.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Jovaisa T, Laurinenas G, Vosylius S, Sipylaite J, Badaras R, Ivaskevicius J (2006). Effects of ketamine on precipitated opiate withdrawal. Medicina (Kaunas) 42 (8): 625–34.

- ↑ Lunch ish M, Clark A, Sawynok J, Sullivan M (2005). Topical amitriptyline and ketamine in neuropathic pain syndromes: an open-label study. J Pain 6 (10): 644–9.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Elia N, Tramèr M (2005). Ketamine and postoperative pain--a quantitative systematic review of randomised trials. Pain 113 (1-2): 61–70.

- ↑ Saito O, Aoe T, Kozikowski A, Sarva J, Neale J, Yamamoto T (2006). Ketamine and N-acetylaspartylglutamate peptidase inhibitor exert analgesia in bone cancer pain. Can J Anaesth 53 (9): 891–8.

- ↑ Adams H (1997). [S-(+)-ketamine. Circulatory interactions during total intravenous anesthesia and analgesia-sedation]. Anaesthesist 46 (12): 1081–7.

- ↑ Log In Problems

- ↑ Blackwell Publishing Press Room

- ↑ Correll GE, Futter GE (2006). Two case studies of patients with major depressive disorder given low-dose (subanesthetic) ketamine infusions. Pain Med 7 (1): 92–5.

- ↑ NIH. "Experimental Medication Kicks Depression in Hours Instead of Weeks" NIH News, August 7, 2006

- ↑ Khamsi, R. "Ketamine relieves depression within hours" New Scientist, 8 August 2006.

- ↑ Zarate C, Singh J, Carlson P, Brutsche N, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh D, Charney D, Manji H (2006). A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63 (8): 856–64.

- ↑ Berman R, Cappiello A, Anand A, Oren D, Heninger G, Charney D, Krystal J (2000). Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry 47 (4): 351–4.

- ↑ Liebrenz M, Borgeat A, Leisinger R, Stohler R. Intravenous ketamine therapy in a patient with a treatment-resistant major depression. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007 April 21;137(15-16):234-6

- ↑ Goforth HW, Holsinger T (2007). Rapid relief of severe major depressive disorder by use of preoperative ketamine and electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT 23 (1): 23–5.

- ↑ "NIMH. "Faster-Acting Antidepressants Closer to Becoming a Reality." July 25, 2007, http://www.nimh.nih.gov/press/ketamine_2.cfm

- ↑ Krystal AD, Weiner RD, Dean MD, et al (2003). Comparison of seizure duration, ictal EEG, and cognitive effects of ketamine and methohexital anesthesia with ECT. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 15 (1): 27–34.

- ↑ Kudoh A, Takahira Y, Katagai H, Takazawa T (2002). Small-dose ketamine improves the postoperative state of depressed patients. Anesth. Analg. 95 (1): 114–8, table of contents.

- ↑ Garcia LS, Comim CM, Valvassori SS, et al (2008). Acute administration of ketamine induces antidepressant-like effects in the forced swimming test and increases BDNF levels in the rat hippocampus. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 32 (1): 140–4.

- ↑ The Combination of Psychedelic and Aversive Approaches in Alcoholism Treatment - Eleusis

- ↑ Krupitsky EM, Grinenko AY. Ketamine psychedelic therapy (KPT): a review of the results of ten years of research. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1997 Apr-Jun;29(2):165-83. Review.

- ↑ http://www.eleusis.us/resource-center/references/ketamine-psychotherapy-heroin.pdf

- ↑ 26. Krupitsky EM, Burakov AM, Dunaevsky IV, Romanova TN, Slavina TY, Grinenko AY. Single versus repeated sessions of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for people with heroin dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007 Mar;39(1):13-9. PMID: 17523581 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

- ↑ Michael J. Winkelman and Thomas B., Roberts (editors) Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood

- ↑ [1] Goldberg ME, Domsky R, Scaringe D, Hirsh R, Dotson J, Sharaf I, Torjman MC, Schwartzman RJ. "Multi-day low dose ketamine infusion for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome".Pain Physician. 2005 Apr;8(2):175-9.

- ↑ Correll GE, Maleki J, Gracely EJ, Muir JJ, Harbut RE. Subanesthetic ketamine infusion therapy: a retrospective analysis of a novel therapeutic approach to complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med. 2004 Sep;5(3):263-75.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 [2] CNN report on ketamine therapy for CRPS/RSD September 1, 2006

- ↑ Kiefer RT, Rohr P, Ploppa A, Altemeyer KH, Schwartzman RJ. Complete recovery from intractable complex regional pain syndrome, CRPS-type I, following anesthetic ketamine and midazolam. Pain Pract. 2007 Jun;7(2):147-50.

- ↑ Lundberg, George D. Postoperative Ketamine Can Reduce Morphine Consumption and Nausea. Medscape. URL accessed on 2008-11-04.

- ↑ Togal T, Demirbilek S, Koroglu A, Yapici E, Ersoy O. (2004). Effects of S(+) ketamine added to bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia for prostate surgery in elderly patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol 21 (3): 193–197.

- ↑ Fort Dodge (devision of Wyeth) Ketamine Lable. Article retrieved on 1 Nov 2008

- ↑ Kelland et al. (1993)Physiol Behav. 54(3):547-54.PMID: 8415949

- ↑ Chen et al. (2009), J Neurosci. 29(3):600-609;PMID 15958747

- ↑ Carr et al. (2007) J Physiol. 584(2): 437-450; PMID 17702809

- ↑ Chen et al. (2009), J Neurosci. 29(3):600-609;PMID 15958747

- ↑ Coates KM, Flood P (October 2001). Ketamine and its preservative, benzethonium chloride, both inhibit human recombinant alpha7 and alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 134 (4): 871–9.

- ↑ Togal T, Demirbilek S, Koroglu A, Yapici E, Ersoy O. Effects of S(+) ketamine added to bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia for prostate surgery in elderly patients. European Journal of Anaesthesiology (2004), 21: 193-197.

- ↑ Benoit E (1995). Effects of intravenous anaesthetics on nerve axons. Eur J Anaesthesiol 12 (1): 59–70.

- ↑ Wagner L, Gingrich K, Kulli J, Yang J (2001). Ketamine blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels: evidence for a shared receptor site with local anesthetics. Anesthesiology 95 (6): 1406–13.

- ↑ Shibuta S, Varathan S, Mashimo T. Ketamine and thiopental sodium: individual and combined neuroprotective effects on cortical cultures exposed to NMDA or nitric oxide. Br J Anaesth. 2006 Oct;97(4):517-24. Epub August 23 2006.

- ↑ SI.com - More Sports - The Mexican Connection (cont.) - Wednesday July 18, 2007 3:35PM

- ↑ Untitled-59

- ↑ ABC News: Ketamine, a Tranquilizer and Popular Club Drug, May Work for Depression

- ↑ Saunders, N., & Heron, L., (1993) E for Ecstasy (Paperback), N. Saunders, London. (ISBN 0950162884)

- ↑ See: [3] for details online.

- ↑ Erowid Ketamine Vault: Dosage

- ↑ AJ Giannini, RH Loiselle, MC Giannini, WA Price. Phencyclidine and the dissociatives. Medical Psychiatry. 3(3):197-204, 1987.

- ↑ AJ Giannini,RH loisellle, MC Giannini, WA Price, 1987, op. cit.

- ↑ AJ Giannini,N Underwood, M Condon. Acute ketamine intoxication treated by haloperidol.American Journal of Therapeutics. 7:389-743,2000, PMID 11304647.

- ↑ AJ Giannini. Drugs of Abuse:Second Edition. Los Angeles,Practice Management Information Company,1997. ISBN 1-57066-053-0.

- ↑ Olney J, Labruyere J, Price M (1989). Pathological changes induced in cerebrocortical neurons by phencyclidine and related drugs. Science 244 (4910): 13ggyryteyt60–2.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Erowid DXM Vaults: Health: The Bad News Isn't In: A Look at Dissociative-Induced Brain Damage, by Anderson C

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Tryba M, Gehling M. Clonidine--a potent analgesic adjuvant. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2002 Oct;15(5):511-7

- ↑ Hargreaves R, Hill R, Iversen L. Neuroprotective NMDA antagonists: the controversy over their potential for adverse effects on cortical neuronal morphology. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 60: 15–9.

- ↑ AJ Giannini, N Underwood, M Condon op. cit.

- ↑ BMJ - Urinary tract disease associated with chronic ketamine use

- ↑ Shahani R, Streutker C, Dickson B, Stewart RJ. Ketamine-associated ulcerative cystitis: a new clinical entity. Urology. 2007 May;69(5):810-2.

- ↑ http://www.barethemusical.com/about/

- ↑ See List of Bones episodes

External links[]

- EMCDDA Report on the risk assessment of ketamine in the framework of the joint action on new synthetic drugs

- eMedicine: Ketamine Emergency Applications

- Erowid.org's John C. Lilly Vault

- Ketamine Dreams and Realities by Karl Jansen MD: thorough book, excellent on society's dysfunctional fear of psychedelics

- Eleusis References on the uses of ketamine as an entheogen for treating alcoholism, the use of ketamine in psychiatry, and for treating drug addiction

- Radical Relief Use of ketamine as an agent to "reboot" the brain of a patient in chemically induced coma to greatly diminish chronic pain.

- Club drug finds use as antidepressant - Psychedelic ketamine hits the blues surprisingly fast; Nature.com

- Rehab clinic in Puerto Penasco Mexico that uses ketamine to detox it's patients from opiates

- Ketamine and Depression Science Friday mp3 podcast about new research in biological psychiatry and ketamine

Dissociative hallucinogens |

|---|

|

2-MDP - Dexoxadrol - Dextromethorphan - Dizocilpine - Efavirenz - Esketamine - Etoxadrol - Ketamine - Muscimol - Nitrous oxide - PCE - PCP - PCPy - Salvinorin A - Pentazocine - TCP - Tifluadom - Tiletamine - Xenon |

Template:Glutamate receptor ligands

Anesthetic: General anesthetics (N01A) | |

|---|---|

| Barbiturates |

Hexobarbital, Methohexital, Narcobarbital, Thiopental |

| Ethers |

Diethyl ether, Desflurane, Enflurane, Isoflurane, Methoxyflurane, Methoxypropane, Sevoflurane, Vinyl ether |

| Haloalkanes |

Chloroform, Halothane, Trichloroethylene |

| Opioids |

Alfentanil, Anileridine, Fentanyl, Phenoperidine, Remifentanil, Sufentanil |

| Others |

Alfaxalone, Droperidol, Etomidate, gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid, Ketamine/Esketamine, Minaxolone, Nitrous oxide, Propanidid, Propofol, Xenon |

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |