Assessment |

Biopsychology |

Comparative |

Cognitive |

Developmental |

Language |

Individual differences |

Personality |

Philosophy |

Social |

Methods |

Statistics |

Clinical |

Educational |

Industrial |

Professional items |

World psychology |

Philosophy Index: Aesthetics · Epistemology · Ethics · Logic · Metaphysics · Consciousness · Philosophy of Language · Philosophy of Mind · Philosophy of Science · Social and Political philosophy · Philosophies · Philosophers · List of lists

| Platonism |

| Platonic idealism |

| Platonic realism |

| Middle Platonism |

| Neoplatonism |

| Articles on Neoplatonism |

| Platonic epistemology |

| Socratic method |

| Socratic dialogue |

| Theory of forms |

| Platonic doctrine of recollection |

| Individuals |

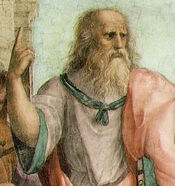

| Plato |

| Socrates |

| Discussions of Plato's works |

| Dialogues of Plato |

| Plato's metaphor of the sun |

| Analogy of the divided line |

| Allegory of the cave

|

Platonic epistemology holds that knowledge is innate, so that learning is the development of ideas buried deep in the soul, often under the mid-wife-like guidance of an interrogator. Plato believed that each soul existed before birth with "The Form of the Good" and a perfect knowledge of everything. Thus, when something is "learned" it is actually just "recalled."

Plato drew a sharp distinction between knowledge, which is certain, and mere opinion, which is not certain. Opinions derive from the shifting world of sensation; knowledge derives from the world of timeless forms, or essences. In the Republic, these concepts were illustrated using the metaphor of the sun, the divided line, and the allegory of the cave.

Metaphor of the sun[]

- For more details on this topic, see Plato's metaphor of the sun.

In The Republic (507b-509c) Plato uses the sun as a metaphor for the source of "intellectual illumination," which he held to be The Form of the Good. The metaphor is about the nature of ultimate reality and how we come to know it. It starts with the eye, which Plato says is unusual among the sense organs in that it needs a medium, namely light, in order to operate. The strongest and best source of light is the sun; with it, we can discern objects clearly. Analogously for intelligible objects The Form of the Good is necessary in order to understand any particular thing. Thus, if we attempt to understand why things are as they are, and what general categories can be used to understand various particulars around us, without reference to any forms (universals) we will fail completely. By contrast, "the domain where truth and reality shine resplendent" is none other than Plato's world of forms--illuminated by the highest of the forms, that of the Good. Since true being resides in the world of the forms, we must direct our intellect there to have knowledge; otherwise, we are stuck with mere opinion of what may be likened to passing shadows.

The divided line[]

- For more details on this topic, see Plato's divided line.

Plato, in The Republic Book VI (509d-513e), uses the literary device of a divided line to teach his basic views about four levels of existence (especially "the intelligible" world of the forms, universals, and "the visible" world we see around us) and the corresponding ways we come to know what exists.

The divided line has two parts that represent the intelligible world and the smaller visible world. Each of those two parts is divided, the segments within the intelligible world represent higher and lower forms and the segments within the visible world represent ordinary visible objects and their shadows, reflections, and other representations. The line segments are unequal and their lengths represent "their comparative clearness and obscurity" and their comparative "reality and truth," as well as whether we have knowledge or instead mere opinion of the objects. Hence, we are said to have relatively clear knowledge of something that is more real and "true" when we attend to ordinary perceptual objects like rocks and trees; by comparison, if we merely attend to their shadows and reflections, we have relatively obscure opinion of something not quite real.

Allegory of the cave[]

- For more details on this topic, see Plato's allegory of the cave.

In his best-known dialogue, The Republic, Plato drew an analogy between human sensation and the shadows that pass along the wall of a cave - an allegory known as Plato's allegory of the cave. Prisoners inside the cave can view only the shadows of puppets in front of a fire behind them. If a prisoner is freed, he learns that his previously perceived reality was merely a "shadow" and that the puppets are more "real." If the learner moves outside of the cave, he/she learns that there are real things of which the puppets are just imitation - a greater reality is again achieved. Thus, opinion is steadily replaced with knowledge; mere opinion is the viewing of the shadows, whereas knowledge is an escape from the cave, into the world of the sun and real objects. Eventually, the learner reaches the "form" of the object through the dialectic.

An example: love and wisdom[]

A good example of how Plato viewed the acquiring of knowledge is contained in his teachings of the Ladder of Love. In Symposium (210a-211b) a "lover" is defined as someone who loves and to love is defined as a desire for something that one does not have. According to this ladder model of love, a lover progresses from rung to rung from the basest love to the pure form of love as follows:

- A beautiful body - The lover begins here at the most obvious form of love.

- All beautiful bodies - If the lover examines his love and does some investigating, he/she will find that the beauty contained in this beautiful body is not original, that it is shared by every beautiful body.

- Beautiful souls - After most likely attempting to have every beautiful body, the lover should realize that if a single love does not satisfy, there is not reason to think that many ones will satisfy. Thus, the "lover of every body" must, in the words of Plato, "bring his passion for the one into due proportion by deeming it of little or of no importance." Instead, the passion is transferred to a more appropriate object: the soul.

- The beauty of laws and institutions - The next logical step is for the lover to love all beautiful souls and then to transfer that love to that which is responsible for their existence: a moderate, harmonious and just social order.

- The beauty of knowledge - Once proceeding down this path, the lover will naturally long for that which produces and makes intelligible good social institutions: knowledge.

- Beauty itself - This is the platonic "form" of beauty itself. It is not a particular thing that is beautiful, but is instead the essence of beauty. Plato describes this level of love as a "wondrous vision," an "everlasting loveliness which neither comes nor ages, which neither flowers nor fades." It is eternal and isn't "anything that is of the flesh" nor "words" nor "knowledge" but is consists "of itself and by itself in an eternal oneness, while every lovely thing partakes of it."

Knowledge concerning other things is similarly gained by progressing from a base reality (or shadow) of the thing sought (red, tall, thin, keen, etc.) to the eventual form of the thing sought, or the thing sought itself. Such steps follow the same pattern as Plato's metaphor of the sun, his allegory of the cave and his divided line; progress brings one closer and closer to reality as each step explains the relative reality of the past.

See also[]

- Plato's metaphor of the sun

- Plato's divided line

- Plato's allegory of the cave

- Platonism

References[]

- Melchert, Norman (2002). The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy, McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-19-517510-7.

- fi:Platonilainen tietoteoria

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |